“I walk out onto this marina, this empty, fallow, unused marina property, and I look and I see this opportunity there,” marina project developer Bob Sonnenblick told The News Herald. “It’s undeveloped, and that’s the key part of it. You don’t really see that many opportunities like this.”

PANAMA CITY — The sunset at the Downtown Panama City Marina is spectacular.

Bright oranges paint the sky and color the water, while a handful of people gather around the bent banister that edges the T-dock to watch, take pictures or maybe fish for grouper. A few people putter around their boats.

But that’s it.

The marina store has closed for the day. The restaurants where people used to dine have long since been torn down. Structural repairs are needed. The grassy field in the center is often empty now that the Pokemon Go app has faded from popularity.

As seven different developers have told Panama City officials over the years, the space is not living up to its potential. Not even close — which is precisely what California-based developer Bob Sonnenblick likes about it.

“I walk out onto this marina, this empty, fallow, unused marina property, and I look and I see this opportunity there,” Sonnenblick said in an interview The News Herald. “It’s a blank canvas. I can lay it out right so it will work. I see this amazing opportunity. It’s undeveloped, and that’s the key part of it. You don’t really see that many opportunities like this.”

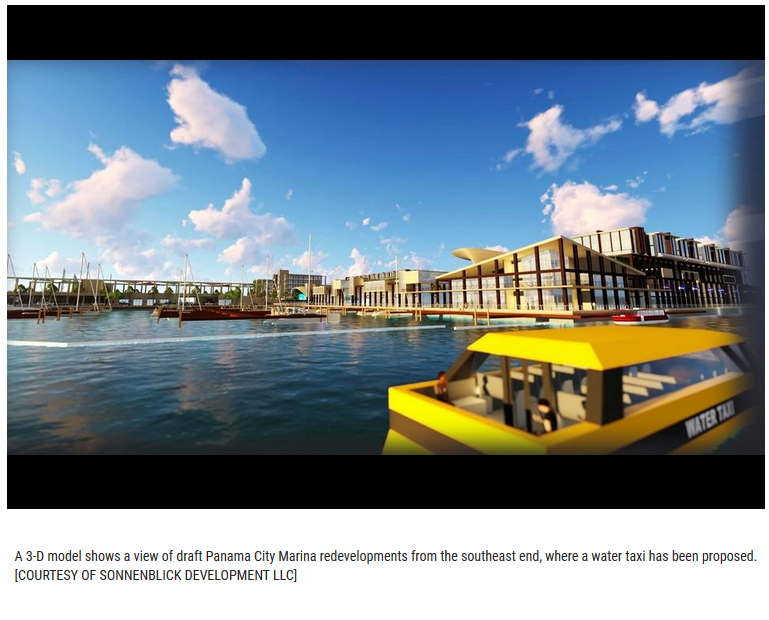

Sonnenblick envisions a place that could become a big tourism draw for the area, with two hotels, an enhanced civic center, retail space, apartments, a splash pad and fishing all around the perimeter. But first he has to pitch his $200 million idea to Panama City commissioners — and residents.

Years in the making

The question of how to best revitalize the marina — and by extension downtown Panama City — has been a perplexing one for years, spanning multiple commissions.

When the city started to really tackle the project in 2011 with consulting company AECOM, the state still held the deed to the marina, which limited the project to a park atmosphere without commercial use. The first concept plan in 2012 featured a lighthouse, a splash pad and the addition of several trees. Ultimately, the planning cost the city $755,576.47.

But it was also right around the time the city’s legal counsel began to question whether the state should, in fact, hold the deed. They took the matter to court and won, which put the land in the city’s control and changed the rules.

Commercial, residential and other uses all became a real possibility. The affair cost the city $108,223.89 — but saved about $89,000 a year for 75 years on submerged ground leases from the state, more than negating the cost.

“In the beginning, we were hamstrung by the deed,” said Mayor Greg Brudnicki, who called the original design an under-utilization of space. “We owed it to people to find out what was possible.”

The commission voted to put the redevelopment out to bid. They gave developers a blank slate, with the only condition being they wanted the project to be an economic driver, as the marina originally was intended to be when it was built by the city in the 1950s.

Proposals came back. The commission whittled it down. Developers dropped out. The city, having already spent $177,308.57 on economists and lawyers, went back to the drawing board.

Sonnenblick came into the picture in May 2016.

‘He’s our guy’

Sonnenblick is the sort of man who shows up to a meetings in a golf polo, responds to emails from almost anyone, uses words like “knucklehead” and pauses during an African safari to leave a voicemail. His quirky personality can at times disguise the lengthy resume that led HomeFed-Leucadia — the company developing Panama City’s SweetBay project — to recommend him for the job.

But here’s his resume: From 1981 to 1991, Sonnenblick completed over $1.5 billion worth of commercial real estate transactions on the West Coast at Sonnenblick-Goldman Corp. of California, including numerous high-end hotels. He then handled multimillion-dollar malls before forming his current company, Sonnenblick

Development LLC, which has worked on projects such as buildings for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He is regularly asked to sit on real estate-related panels.

“He’s our guy,” former Commissioner John Kady used to say, adding people wouldn’t believe the “charlatans” the city has seen. Other commissioners have echoed the sentiment.

But that doesn’t mean every project he’s ever proposed has worked out. Earlier this year, he walked away from a 150-room hotel project near the Sacramento International Airport, according to The Sacramento Bee, after failing to secure funding. And in 2016, he walked away from a project in Pierce County, California, after being asked to scale down the design.

When asked about the Pierce County project, he said he didn’t walk away because of scale, but because of money.

“It’s not a question of walking away because they aren’t grand; it’s a question of walking away because they aren’t financially feasible,” he said. “Those are two different things.”

Finding the sweet spot

The phase where those other projects have fallen apart — the feasibility studies — is the phase Panama City entered into Tuesday night with the commission’s unanimous yes vote to continue the process.

This is the phase that will make or break the deal, when concerns about traffic, utilities, the viability of retail and more will be addressed. As Brudnicki put it, this is “the hard part.”

Between now and February, Sonnenblick will be hiring experts to study every aspect of the proposed design and find what works and what doesn’t.

“I am also going to say to the guys doing the feasibility study, ‘By the way, not only critique what I’ve put on the table, but if you guys have any new ideas you want to throw in, throw it on. Put it on the report. Let’s look at it,’” he said. “I’m totally open to any new ideas that will make the project better, and we’ll find that out over the course of receiving the various feasibility studies.”

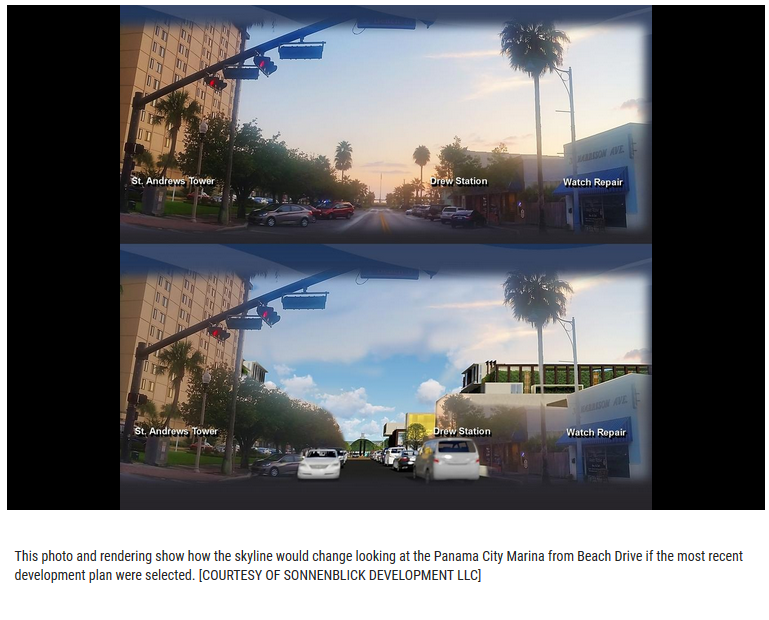

Many people have critiqued the current proposals — which some fear won’t be supported by city infrastructure and ruin sunset views — even before the studies. To them, the rough design process equated to putting the cart in front of the horse.

But Sonnenblick said that’s how development works, using a traffic study as an example.

“The key thing to the traffic study is to define the number of new trips that the project will create, and once you have that number you can then define mitigation or the answers to the problem,” he said. “But in order to define and calculate a number of new trips, you must have designated here are the trip generators. Here are the number of hotel rooms. Here are the number of restaurants. Here are the number of apartments.”

Using the density proposal — Sonnenblick’s current submission to the city — the studies will suggest what can be done and what would break the deal. Continuing to use traffic as an example, Sonnenblick said it’s possible a turning lane would be added on Beach Drive or changes could be made to Luverne Avenue or Grace Avenue. Four-laning Harrison Avenue, he said, is not an option that would be considered.

If, in the end, the feasibility studies don’t work out, the city and Sonnenblick would part ways. No money has been exchanged between the city and Sonnenblick Development at this point, though the city has spent $372,868.40 on its own economist and lawyers to vet the plan, and officials have said the city won’t lose anything but time.

In fact, city officials say the worst-case scenario is that a deal can’t be reached and the city walks away with hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of feasibility studies — paid for by Sonnenblick — that they could hand off to the next interested developer.

If the feasibility studies come back with favorable numbers, the city, which would act as the landlord of the project, would start to work out the details of the deal with Sonnenblick, such as how much rent would be and what incentives, if any, the city would provide.

Changing designs

The design for the marina project will change and change again — and change again — based on the feasibility studies, Sonnenblick has said. But that hasn’t stopped people from forming opinions.

The loudest might be Save the Panama City Marina, a Facebook group that has distributed about 400 lawn signs and some of whose members are vocal critics of the plans so far. About 30 members protested at the most public hearings, saying the development will ruin views, take away public access and kill brick-and-mortar retail. They have said they want a “classic marina.”

The city and Sonnenblick are actively working to address those issues. The city, for instance, is starting to work with the Department of Environmental Protection on building another boat ramp downtown and coming up with a plan to relocate wet-slip tenants during the construction period.

But Sonnenblick also has said that, while he’s listening to the group, it’s not enough to make him turn away from the project.

“There were 30 people out front of City Hall,” he said. “If there were 30 people picketing out of 30,000 residents, that led me even before last week’s city meeting started to be very pleased. Now they’re 30 vocal people, but 30 people out of 30,000 … it’s minuscule.”

Before voting yes, all the commissioners said the majority of people they have spoken to like the current marina concept, though they also said there are parts they don’t like at this point.

But as Commissioner Ken Brown emphasized, chances like this don’t come around every day.

“As far as this marina project, hey, this is the best thing since Carter Liver Pills, I’m gonna tell you,” Brown said. “This is the best thing that is going to happen to Panama City.”